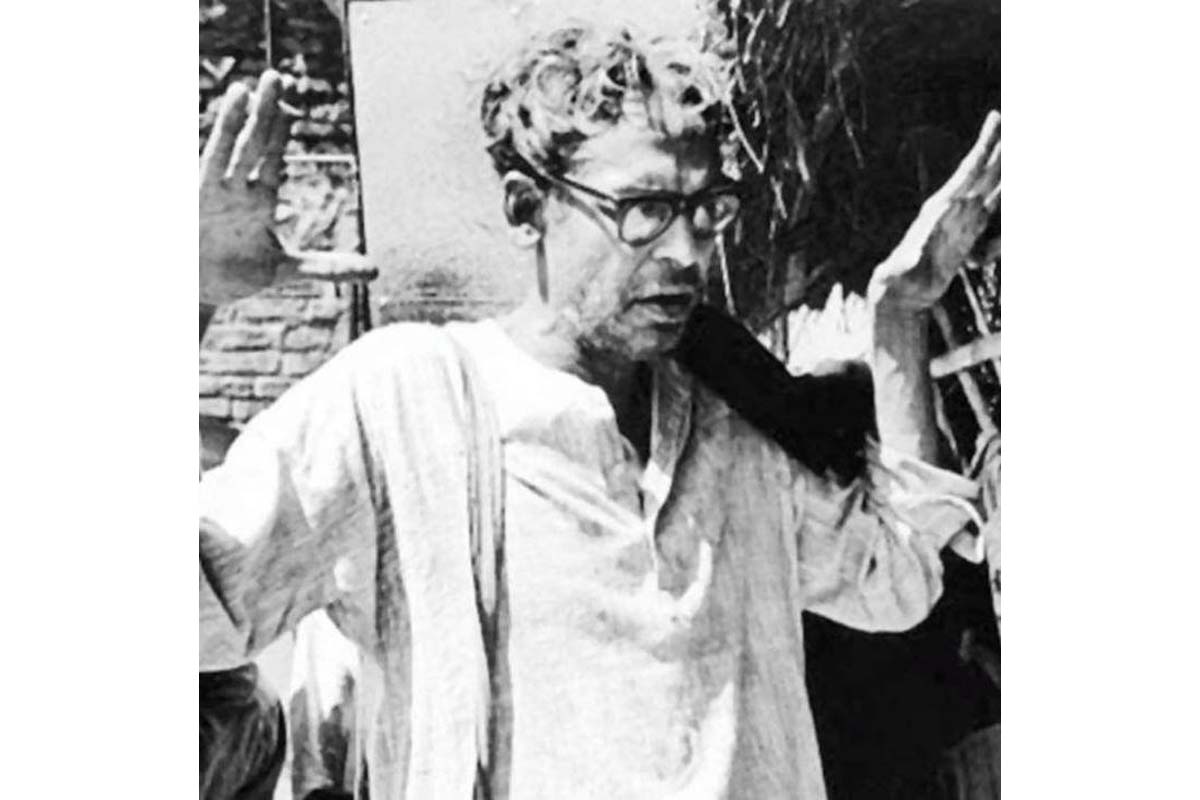

It is no disrespect to his distinguished compatriots to aver that Ritwik Ghatak was arguably the most powerful film-maker that India can boast of. And he was powerful even without the grandstanding at glitzy film festivals. More the pity, therefore, that he must be spinning in his grave. As a film-maker who used the medium to depict the trauma of Partition, he indubitably deserved better than the Bharatiya Janata Yuva Morcha’s attempt to trivialise his classic, Meghe Dhaka Tara, if only to buttress the BJP’s perilously skewed perception of Indian citizenship 72 years after Independence.

Even at the mildest estimation, the morchas strategy suggests an insufficient understanding of the film or even the thematic content of Ghatak’s films generally. His cinema is much too profound to lend scope for a superficial spin. Small wonder that members of his family have taken umbrage to what they call the BJP youth wing’s attempt to “misappropriate” the thematic content of his films for its promotional video in support of two issues of dire contestation ~ the Citizenship Amendment Act and the National Register of Citizens, which is set to be rechristened as the National Population Register.

Advertisement

The change is no more than semantic jugglery to obfuscate the core issue that has roiled the country for a while. It would be presumptuous for the Bharatiya Janata Party to argue that Ghatak’s films cannot be the “property of a single family”. Suffice it to register that no such familial claim has as yet been made. The campaign video could well have been choreographed in keeping with the lights of Amit Shah. There was no call to use a clip from Meghe Dhaka Tara to popularise the BJP youth wing’s video.

Small wonder that as many as 24 members of Ghatak’s family have bared their angst ~ “This act of using any content from his films ~ which does not fit into the context ~ to support a law which seeks re-establishment of identity, talks about the possibility of taking away the citizenship of a particular minority community is deemed unacceptable. It violates the values and principles espoused by Ghatak”. Pre-eminently, he was an ardent believer in humanism and secular ideals”.

He used the medium to depict the plight of refugees and the marginalised, specifically those who were displaced in the post-Partition phase of political and social turbulence. Much as the BJP’s culture brigade claims that “we have every right to use a dialogue from his film”, the fact remains that a cut-and-paste endeavour can be ridiculous when not wholly out of context. The video has made itself vulnerable to both shortcomngs. More than anybody else, Ritwik Ghatak would have balked at such brazen distortion of his cinema, driven by an ideology he never believed in. He deserved better than a puerile controversy 44 years after his passing (1976). The reservations of his family call for reflection. Propaganda is not cinema.